Ormond Simpson. «Hay que hablar de dinero»: apoyo y retención de estudiantes en línea.

(Traducción al español al final del post)

ORMOND SIMPSON

Palabras clave: CUED

“Money, money, money” (Abba)

As I get older I’ve found that I’ve become more and more interested in money. Not personally of course –I would never have gone into teaching otherwise–. But I’ve become concerned about trying to understand the way money is used in online learning.

After all, everything we try to do for our students is depended on the resources we have to teach and support them. Whether that’s improving the quality of our teaching materials or the amount of support we give them, it all comes down to money. But that money is often seen as a barrier – I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve had an idea for improving student support only to be told ‘Sorry – there’s not enough money for that’.

The institution as factory

So think of your institution as a factory. It takes in a raw material – a new student – and invests resources (money) into teaching materials and support for that student. Eventually it hopefully turns out a finished product – a qualified graduate. Now in an actual factory – producing cars say – its managers would have a very clear idea about the relationship between its initial investment and the value of the final car on which it could make a profit. In other words they would undertake a cost-benefit analysis and get a clear idea of the return on their investment. What would happen if we apply that to our student?

Royalty free image downloaded from Pexels

Cost benefits and returns on investment

I focused on student support where it seemed to me we had evidence that could be analysed for financial returns. I worked out that if you had a student support activity costing £P per student which increased student retention by n%, then the ‘cost per student retained’ was £100P/n. (The proof of this equation is naturally left as an exercise to the reader…[1]).

Thus for example, a few years ago in the UKOU we made a pre-course phone call costing £10 per call to new students which appeared to increase retention on their course by about 5%. So the cost per student retained was £(100 x 10)/5 = £200. So far, so absurd. If this figure was correct who could possibly justify spending £200 to retain one student? Well no – until you look at the benefit that one student would bring in.

In those pre-student-loan days the UK Government grant to the UKOU was based on the number of students completing their courses each year, and was about £1100 per student. In addition we reckoned that the more students we retained the fewer we had to recruit the following year to replace the losses and keep student numbers steady. In those days it cost the UKOU nearly £500 to recruit each new student (God knows what it is today). Let’s guess we might save about £100 of that, then the total benefit per student retained in grant income and marketing savings was £(1100 + 100) = £1200.

So we had a cost per student retained of £200 and a benefit per student retained of £1200 – a surplus of £1000 per student retained and a return on investment of 1000/200 = 500% which even a banker might envy.

Other funding arrangements – the UoLIP example.

That was then of course. Now funding arrangements for the UKOU are different and it depends on a combination of government grant and students fees. Similarly other online institutions have a mixture of funding arrangements – do you know all the sources of the money for your institution? The International Programme of the University of London (UoLIP) for example depends on student fees for various different services such as exam fees. So it gets a lot more complicated than my simple £100P/n. And the benefits arise not from any grant, but from successful students carrying and paying another set of fees.

But it’s still possible to do calculations. In my recent paper ‘Student Support in Online Learning—We Need to Talk About Money’[2] I took UoLIP for example, and estimated the following formula for the increase in income from n% extra students taking the exam and re-registering for the next module:

£[(n/100)N(F + E – S – V/N) – NP]

where n, N and P are as before, F = the UoLIP tuition fee, E = the exam fee, V = the institutional overhead and S = the student related cost.

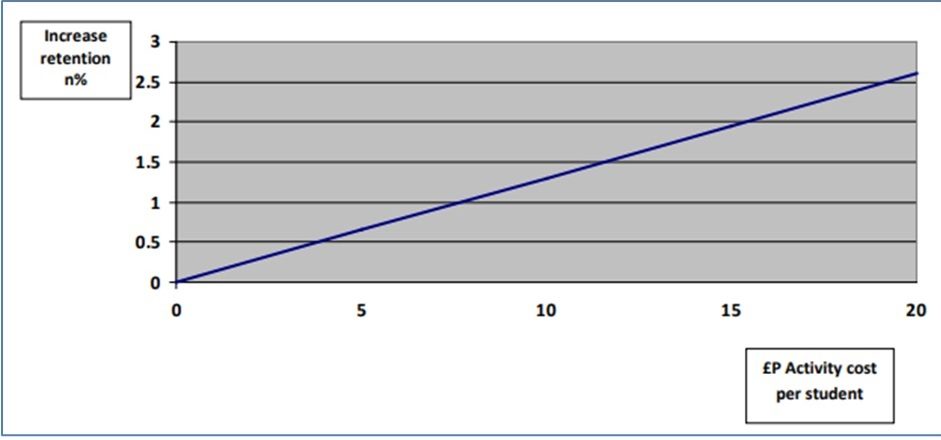

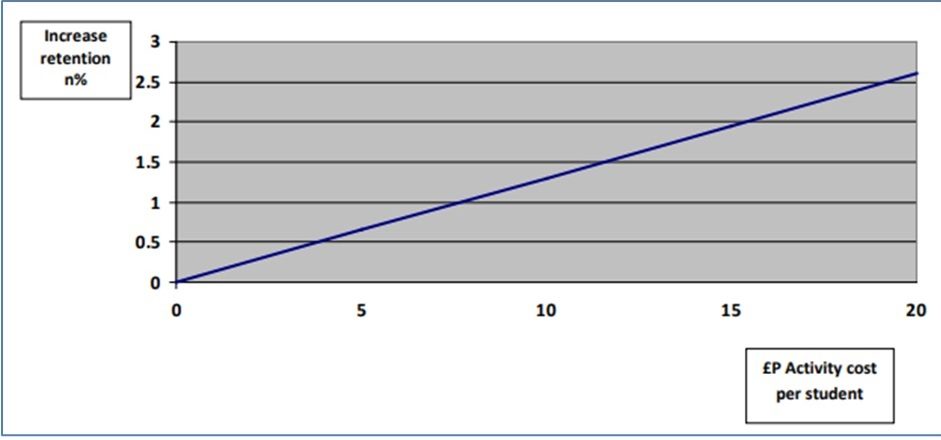

If, like me, your eyes glaze over at this point then you might prefer a graphical representation of the cost £P of an activity versus the increase in retention n% using data from UoLIP:

Increases in retention that fall above the line will produce a positive return for UoLIP. For example an activity cost of £10 that produces an increase in retention of more than about 1.3% will produce a positive return on investment for UoLIP.

Your institution?

Your institution will have different formulas depending on your funding arrangements, the results of retention-increasing activities and their cost. And it may look like an impossibly complex task to understand the money flows involved in increasing student retention. But online institutions are full of highly intelligent analysts, statisticians, accountants, and academics. There is also the potential game changer of artificial intelligence to be applied to student support. It’s high time the talents of such staff be applied to the complex challenges of evaluating the role of money in online learning.

[1] Oh alright. Say you apply your support activity costing £P per student to N students, gaining an increase in retention of n%. Then the total cost is NP and the number of extra students retained is Nn/100 and the cost per student retained is £NP/(Nn/100) = £100P/n.

[2] International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning Volume 24, Number 4

ISSN 1492-3831 https://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/7241/5955

#blogCUED #CátedraUNESCOdeEducaciónaDistancia, #CUED, #asesoresCUED

Cómo referenciar esta entrada:

Simpson, O. (12 de julio de 2024). Online student support and retention. we need to talk about money. Blog CUED https://blogs.uned.es/cued/blog/

Ormond Simpson

Ormond Simpson is a consultant in distance and online education, working most recently as Visiting Fellow at the London University International Programmes. He was previously Visiting Professor at the Open Polytechnic of New Zealand, and Director of the Centre for Educational Guidance and Student Support at the UK Open University, being one of the greatest experts in drop-out prevention in distance education.

He has worked, given keynote presentations and run workshops in 17 countries in Africa, South America, India, China, the West Indies, South Korea, and Europe. His latest book is ‘Supporting Students for Success in Online and Distance Education’ (2012, Routledge).

He has written many book chapters and journal articles. As he says, he originally graduated with a degree in theoretical physics, but he believes that the task of developing really effective distance student support is just as challenging as finding a Theory of Everything…

Hay que hablar de dinero»: apoyo y retención de estudiantes en línea

«Dinero, dinero, dinero» (Abba)

A medida que me hago mayor me interesa cada vez más el dinero. No personalmente, por supuesto, porque de lo contrario nunca me habría dedicado a la enseñanza. Pero me he preocupado por intentar comprender cómo se utiliza el dinero en la enseñanza en línea.

Al fin y al cabo, todo lo que intentamos hacer por nuestros alumnos depende de los recursos de que disponemos para enseñarles y apoyarles. Ya se trate de mejorar la calidad de nuestro material didáctico o de la cantidad de apoyo que les damos, todo se reduce a dinero. He perdido la cuenta de las veces que he tenido una idea para mejorar el apoyo a los estudiantes y me han dicho: «Lo siento, no hay dinero suficiente para eso».

La institución como fábrica

Piense en su institución como en una fábrica. Recibe una materia prima -un nuevo estudiante- e invierte recursos (dinero) en material didáctico y apoyo para ese estudiante. Al final, con un poco de suerte, obtiene un producto acabado: un titulado cualificado. Ahora bien, en una fábrica real, por ejemplo, de coches, sus directivos tendrían una idea muy clara de la relación entre la inversión inicial y el valor del coche final con el que podrían obtener beneficios. En otras palabras, realizarían un análisis coste-beneficio y tendrían una idea clara del rendimiento de su inversión. ¿Qué pasaría si aplicamos eso a nuestro alumno?

Coste-beneficio y rendimiento de la inversión

Me centré en el apoyo a los estudiantes allí donde me pareció que teníamos pruebas que podían analizarse en función de la rentabilidad financiera. Calculé que si una actividad de apoyo a los estudiantes costaba P£ por estudiante y aumentaba la retención de estudiantes en un n%, el «coste por estudiante retenido» era de £100P/n. (La demostración de esta ecuación se deja naturalmente como ejercicio para el lector… ).

Así, por ejemplo, hace unos años en la UKOU realizamos una llamada telefónica previa al curso a los nuevos estudiantes, con un coste de 10 libras por llamada, que parecía aumentar la permanencia en el curso en un 5% aproximadamente. Así que el coste por estudiante retenido fue de £(100 x 10)/5 = £200. Hasta aquí, absurdo. Si esta cifra fuera correcta, ¿quién podría justificar el gasto de 200 libras para retener a un estudiante? Pues nadie… hasta que se analiza el beneficio que aportaría un estudiante.

En aquella época anterior a los préstamos a estudiantes, la subvención del Gobierno británico a la UKOU se basaba en el número de estudiantes que terminaban sus cursos cada año, y era de unas 1.100 libras por estudiante. Además, calculábamos que cuantos más estudiantes retuviéramos, menos tendríamos que contratar al año siguiente para compensar las pérdidas y mantener estable el número de estudiantes. En aquella época, a la UKOU le costaba casi 500 libras contratar a cada nuevo estudiante (Dios sabe cuánto cuesta hoy en día). Supongamos que nos ahorrábamos unas 100 libras, por lo que el beneficio total por estudiante retenido en ingresos por becas y ahorro en marketing era de (1.100 + 100) = 1.200 libras.

Así que tuvimos un coste por estudiante retenido de 200 £ y un beneficio por estudiante retenido de 1200 £ – un superávit de 1000 £ por estudiante retenido y un rendimiento de la inversión de 1000/200 = 500% que incluso un banquero podría envidiar.

Otros mecanismos de financiación: el ejemplo del UoLIP.

Eso era entonces, por supuesto. Ahora, la financiación de la UKOU es diferente y depende de una combinación de subvenciones públicas y tasas de matrícula. Del mismo modo, otras instituciones en línea tienen una combinación de mecanismos de financiación. ¿Conoce todas las fuentes de financiación de su institución? El Programa Internacional de la Universidad de Londres (UoLIP), por ejemplo, depende de las tasas que pagan los estudiantes por distintos servicios, como las tasas de examen. Así que la cosa se complica mucho más que mis simples £100P/n. Y los beneficios no proceden de ninguna subvención, sino de que los estudiantes que aprueban llevan consigo y pagan otra serie de tasas.

Pero aún es posible hacer cálculos. [1]En mi reciente artículo «Student Support in Online Learning-We Need to Talk About Money» (Apoyo a los estudiantes en el aprendizaje en línea: tenemos que hablar de dinero) tomé como ejemplo el UoLIP y calculé la siguiente fórmula para el aumento de ingresos derivado de que un n% más de estudiantes se presentaran al examen y se volvieran a matricular en el siguiente módulo:

£[(n/100)N(F + E – S – V/N) – NP]

donde n, N y P son como antes, F = la tasa de matrícula UoLIP, E = la tasa de examen, V = los gastos generales institucionales y S = el coste relacionado con el estudiante.

Si, como a mí, se le nublan los ojos en este punto, tal vez prefiera una representación gráfica del coste £P de una actividad frente al aumento de la retención n% utilizando datos de UoLIP:

Los aumentos de la retención que se sitúen por encima de la línea producirán un rendimiento positivo para UoLIP. Por ejemplo, un coste de actividad de 10 £ que produzca un aumento de la retención superior al 1,3% aproximadamente producirá un rendimiento positivo de la inversión para UoLIP.

¿Su institución?

Su institución tendrá fórmulas diferentes en función de sus acuerdos de financiación, los resultados de las actividades de aumento de la retención y su coste. Y puede parecer una tarea imposiblemente compleja comprender los flujos monetarios que intervienen en el aumento de la retención de estudiantes. Pero las instituciones en línea están llenas de analistas, estadísticos, contables y académicos muy inteligentes. También existe el potencial de cambio de juego de la inteligencia artificial para aplicarla al apoyo a los estudiantes. Ya es hora de que el talento de este personal se aplique a los complejos retos de evaluar el papel del dinero en el aprendizaje en línea.

[1] Revista Internacional de Investigación sobre Aprendizaje Abierto y Distribuido Volumen 24, Número 4

ISSN 1492-3831 https://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/7241/5955

![]()