English

Breaking down paradigms Palaeolithic art for the 21st century From dark caves to sunny plains Defending your heritage Sponsor an archaeologist

- About the project

- Your involvement

- Precedents

- Impact

- Archaeological Heritage

Since the 19th century, prehistorians of palaeolithic art have focused their research primarily on closed environments such as caves and rock shelters.

To the surprise of many specialists, and only for around the past three decades, outdoor Palaeolithic rock art has begun to be highly valued.

Initial studies focused on the Duero, Tajo and Guadiana river basins. But as studies have increased, samples of this outdoor art have been appearing at different points across our peninsula. And many of them, curiously, at altitudes far above sea level.

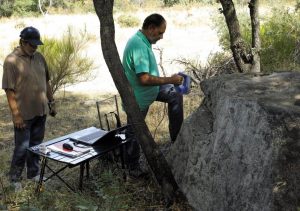

A team of archaeologists from the UNED is researching open-air Palaeolithic art in Spain and invites you to participate in the 2025 campaign.

you to participate in the 2025 campaign.

The 2025 campaign includes training seminars, online workshops, analysis of the participants’ findings, guided tours, fieldwork by the researchers, and will be funded by crowdfounding.

Palaeolithic rock art is one of the most complex signs handed down to us from our ancestors

With more than 800 sites spread throughout the Old Continent, we can get a fairly approximate idea of the themes, techniques, and their spatial distribution in closed environments such as caves and rock shelters.

For about thirty years we have also known about outdoor Palaeolithic rock art, with a much lower proportion in terms of sites but not when it comes to the number of ideograms.

This art is located in the Duero, Tajo and Guadiana river basins and is always made on shale or slate outcroppings.

Although at first these types of forms were slow to be accepted as Palaeolithic because they were not found in karst landscapes, today nobody doubts their Pleistocene parentage.

Picket horse from Piedras Blancas (Almería), discovered in 1987.

It is society that finances our research and it is to it that we must return the investment. From experience, we know that when we offer the possibility of participating in a cultural activity, people will take part in it and demand more, regardless of their age or level of education.

Furthermore, the results expected from this research project would have a major impact on the international scientific community.

With our working method, both materially and conceptually, if the immense and complex task of revising all the stations with Palaeolithic cave art were to be undertaken, it would undoubtedly lead to the rediscovery of a universe based on a communication system that we have barely glimpsed. It would change our knowledge of the economic and material achievements of our ancestors and, above all, of their thinking, as the catalogue of cave paintings and engravings would undoubtedly increase considerably.

A large collection of fauna and flora is represented in the rock art, which can be related to the environment and climate at the time the pictograms were made, making it a great collection of natural history.

However, for a couple of years now, a series of groups have been appearing all over the peninsula, which for the moment cannot be included in the aforementioned categories, although most of them would be closer to the second one. These groups have similar characteristics to those that are fully accepted, but at the same time they differ in certain concepts. These distinctions are mainly centred on their geographical situation, type of support and its location. Some assemblages appear at a high altitude above sea level. This would conflict with the environmental conditions at the end of the last ice age and would raise new hypotheses about the mobility of hunter-gatherer groups. Others are in areas where there is a long tradition of prehistoric studies and it seems strange that none of the great specialists who have preceded us would not have noticed these numerous naturalistic figures. Likewise, there are other areas where there has been no notable research into Palaeolithic settlement and where representations appear not only in shelters or caves, but also in the open air. In other cases, the surprise lies in the rocky support on which the representations are made. Normally, until now, only figures on granite have been attributed to post-Palaeolithic schematic art, but the evidence shows that our Palaeolithic predecessors also used this type of support on a regular basis.

Specifically, this project focuses on the study of the following sites, some of which already have preliminary studies:

– Lleida: Río Garona (Valle de Arán), granite, outdoor.

– Palencia: Cañón de La Horadada (Aguilar de Campoo), 24 cavities, 179 rock shelters and outdoor blocks, limestone.

– Ávila: El Barraco (Arroyo Arrejondo) y Candeleda, outdoor, granite. La Peña de la Cueva (Ojos Albos), rock shelter and outdoor, limestone.

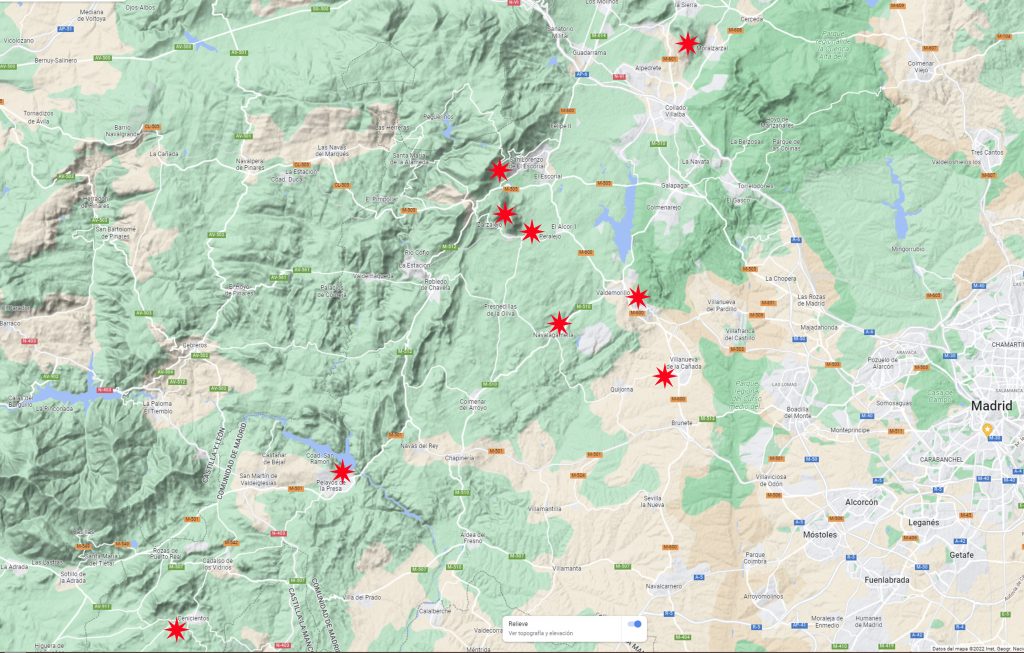

– Madrid: Sierra Oeste, granite, outdoor, portable art. This covers an area of 110 kilometres with many locations ranging from Cenicientos in the southwest to Moralzarzal in the northeast, passing through Pelayos de la Presa, Villanueva de la Cañada, Valdemorillo, Zarzalejo estación, El Escorial, La Pedriza, etc. In a provisional recounting, the set contains more than 20,000 figures. The Ministry of Culture in the Community of Madrid has declared the entire set, which we continue to work on, a Cultural Interest site (BIC). Also in the area of Villanueva de la Cañada we have found a large outdoor site with numerous small rocks, small blocks and platelets of calcarenite as well as quartzite with numerous engraved figures which constitutes the first site with Palaeolithic portable art from the interior of the peninsula.

– Valencia: Barranco Ripoll (Buñol), rock shelters and outdoor, limestone.

– Murcia: Cueva de los Cascarones (Moratalla), rock shelter, outdoor, limestone. Cala Déntoles y Cala Reona (Cartagena), rock shelter and outdoor, sandstone.

Most of the sites we have identified so far are located in isolated areas, far from large urban centres. The existence of this rich heritage will make it possible to attract young people to the area by creating information centres and guided tours of the various sites.

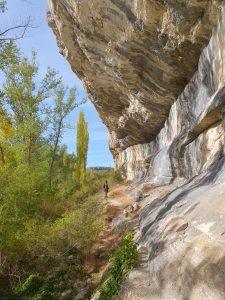

As they are quite remote areas, these open-air Palaeolithic rock art sites on different stone supports are immersed in natural environments of great scenic and faunal richness.

Obviously it will not have an immediate impact on rural areas, but a correct dissemination in the media and in local and provincial institutions will create interest in knowing this new heritage bequeathed by our ancestors, being the first and oldest expression of human thought that has come down to us in the form of images and signs. We are talking not only about a language or a metalanguage of images that reflect it, but also about an important set of data that is beginning to be of fundamental importance in our history and probably for our species.

The enhancement of these new findings will undoubtedly contribute to the economic and social development of the regions where these sites are located, as a magnet for sustainable tourism and a revitalising element for the so-called ‘emptied’ Spain. Likewise, the dissemination of their historical heritage among the local population will certainly contribute to the inhabitants of these territories becoming the first defenders of their conservation and placing themselves in the first line of defence for their protection.

Why now, and why hasn’t anyone seen it until now?

One hundred and forty-one years ago Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola discovered the Altamira Cave. The scientific community of the time vilified this unique discovery and the distinguished researcher died without seeing its authenticity recognised.

Until about 35 years ago, a few open-air sites with so-called ‘Palaeolithic style’ representations were known, which were incorporated into the synthesis either marginally or in the form of footnotes. However, since the beginning of the 1990s, numerous outdoor Palaeolithic art groups have been appearing, mainly on shale supports. Today, no one denies their existence and importance.

A couple of years ago, by chance, thanks to a combination of the right sunlight and the experience accumulated in the study of Palaeolithic fine line engravings, we identified a series of incised figures in the open air, on granite. Until then, the researchers had been looking for painted or engraved figures on granite supports that could be classified as Neolithic and Metal Age schematic art.

The existence of immense Palaeolithic rock art sites scattered over wide geographical areas dismantled the current paradigm on rock art. It had always been thought that Palaeolithic figures were located in closed environments (caves) where mystical practices enhanced the power of the images.

Today, however, we believe that this landmark has been totally transformed. Outdoor art was the norm and cave art was the rarity. We have moved from the darkness of caves to sunny environments.

We needed to find an identification pattern that would allow us to locate more evidence in other areas, starting from the original core of the Sierra Oeste de Madrid. Today, this pattern has led us to previously unthinkable areas such as the high mountains, the plateau or the Mediterranean coast.

Why is there so much of it?

In order to try to establish a chronological framework, in our studies we use a series of stylistic conventions that allow us to date the different assemblages more or less precisely. So far we can state with more or less precision that most of them are from the Upper Solutrean to the Middle Magdalenian. That is to say, about 6,000 years in duration. And between 22,000 and 16,000 years before the present.

This long time span can be translated into 18,000 generations of ancestors following pre-established routes and repeatedly carving those animals that caught their attention or that they had hunted, re-engraving over and over again on the same surfaces. Natural erosion on these stone supports allows us to identify the bottom of the engraved grooves, as opposed to closed environments where the incisions are perfectly preserved and therefore deeper.

Before we launch the campaign, we need to know if you would like to participate in the activities and make a donation. Please fill in the questionnaire at the link with your preferences:

LINK TO THE FORM

We ask you to distribute this questionnaire as widely as possible.

RESEARCH TEAM

Fco Javier Muñoz Ibáñez

Licenciado en Prehistoria y Arqueología por la Facultad de Geografía e Historia de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid en 1993. Doctor en Geografía e Historia, especialidad Prehistoria y Arqueología por la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia en 1998. En la actualidad soy Profesor Contratado Doctor del Departamento de Prehistoria y Arqueología de la UNED impartiendo las asignaturas de "Prehistoria I," "Prehistoria II" y "De cazadores a productores" del Grado de Geografía e Historia y "La cultura material como fuente esencial de conocimiento en Arqueología" del Máster Universitario en Métodos Y Técnicas Avanzadas de Investigación Histórica, Artística y Geográfica. He participado en numerosos proyectos de investigación, tanto nacionales como internacionales, cuyos resultados se han plasmado en diversas monografías y numerosos artículos. Mi línea de investigación se ha centrados en el Paleolítico Superior, abordando diferentes cuestiones relacionadas con la evolución tecnológica del instrumental cinegético, la balística y arquería prehistóricas, la Arqueología experimental o el arte paleolítico. En esta última línea de investigación he participado en el estudio de numerosas estaciones de arte paleolíticas como Domingo García y la Peña de Estabanvela (Segovia), Maltravieso (Cáceres), Creswell Crags (Reino Unido), La Cueva de Ambrosio (Almería), El Moro (Cádiz), La Fuente del Trucho (Huesca) y en los nuevos yacimientos de arte rupestre al aire libre.

Sergio Ripoll López

Licenciado en Historia por la Universidad Central de Barcelona (1981), obteniendo el título de Licenciado con Grado en la Universidad de León. Doctor en Prehistoria por la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia en 1988. Los trabajos de investigación llevados a cabo en varias zonas de la Península Ibérica, se ha centrado fundamentalmente en el Paleolítico Superior. La Cueva de Ambrosio (Almería) o La Peña de Estebanvela (Segovia) son algunos de los yacimientos excavados, mientras que El Moro (Cádiz), La Fuente del Trucho (Huesca), o Domingo García (Segovia), son algunas de las estaciones con arte rupestre analizadas. La labor como coordinador del Inventario Nacional de Arte Rupestre entre los años 1981 y 1987 con el Ministerio de Cultura, supuso la documentación de la práctica totalidad de las cavidades conocidas en nuestro país aportándole una gran experiencia en el estudio y análisis de este tipo de manifestaciones. Descubridor del primer arte rupestre paleolítico del Reino Unido (2003) donde ha desarrollado varios proyectos de investigación. Numerosas publicaciones tanto artículos como monografías, son la prueba de esta labor investigadora durante casi 30 años. La labor docente se ha centrado en la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, donde compagina la docencia de la asignatura de Prehistoria I y Prehistoria II de primer curso del Grado en Geografía e Historia y el Máster de la Facultad con la coordinación del Trabajo de Fin de Grado del Departamento. Es miembro de número de varias academias y del Instituto de Estudios Almerienses.

Manuel García Rodríguez

Teacher of Geology, Hydrology, Hydrogeology, Waste Management, Soil Science, Land Resources and Geological Hazards at different universities. He has participated in 20 research projects, national and international, and is author of over ninety scientific and educational publications, on geology, geomorphology and environment and hydrology.

Vicente Expósito Gil

Graduado en Geografía e Historia por la UNED en 2021. Doctor en Historia (especialidad Prehistoria) por la Universidad

Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED) en 2022. Funcionario de carrera de la Administración Local (Ayuntamiento de Valencia). Sus trabajos de prospección, colaboraciones y publicaciones se centran en el estudio del Arte Rupestre. Diversas intervenciones como en el proyecto Velad en Vélez- Blanco en Almería (2015), La Horadada en Palencia (2021), Barranco Ripoll, fuente el Roquillo y márgenes del río Buñol, en Valencia (2022) y Cala Déntoles y Cala Reona en Murcia (2023).

WORK TEAM

Vicente Bayarri Cayón

Universidad Europea del Atlántico

GIM Geomatics

Alía Vázquez Martínez

Universidade de Santigo de Compostela

David Martín Freire- Lista

Universidade de Trás- Os-Montes e Alto Douro

Elena Castillo López

Universidad de Cantabria

Alfredo Maximiano Castillejo

Humanidades Digitales

José Latova Fernández-Luna

Fotógrafo de patrimonio

Sergio Velasco Muñoz

UNED

Laboratorio de Estudios Paleolíticos

Jose Luis García Sánchez

UNED

Laboratorio de Estudios Paleolíticos

EL VALLE DE LAS PIEDRAS SAGRADAS

Paleolithic rock art, previously considered exclusive to caves, can also be found in the open air, as in El Encinar (Ávila) and La Candelaria (Madrid), where millenary engravings of deer and horses have come to light almost by chance. These findings, analyzed with advanced technology, show the richness of our prehistoric heritage. Protecting and studying these remains is essential to preserve the memory and evolution of humanity.

Francisco Javier Muñoz Ibáñez: Profesor del Departamento de Prehistoria y Arqueología, UNED.

Sergio Ripoll López: Catedrático Departamento Prehistoria y Arqueología, UNED.

Vicente I. Sánchez, realización.